The term is often applied generally (and pejoratively) to histories that present the past as the inexorable march of progress towards enlightenment… Whig history has many similarities with the Marxist-Leninist theory of history, which presupposes that humanity is moving through historical stages to the classless, egalitarian society to which communism aspires… Whig history is a form of liberalism, putting its faith in the power of human reason to reshape society for the better, regardless of past history and tradition. In general, Whig historians emphasize the rise of constitutional government, personal freedoms, and scientific progress. Whig history… presents the past as an inevitable progression towards ever greater liberty and enlightenment, culminating in modern forms of liberal democracy and constitutional monarchy. Wikipedia has an excellent opening definition of Whig history: The word has many uses (social progress, technological progress), but the reason it raises red flags for historians is the legacy of Whig history, a school of historical thought whose influence still percolates through many of our models of history. Progress - change for the better over historical time. This is a historian’s succinct if somewhat technical way of asking a question which lies at the back of a lot of the questions people are wrestling with now. “How do you discuss progress without getting snared in teleology?” a colleague asked during a teaching discussion. Part 1: The Question of Progress As Historians Ask It

Two threads, which I will later bring together.

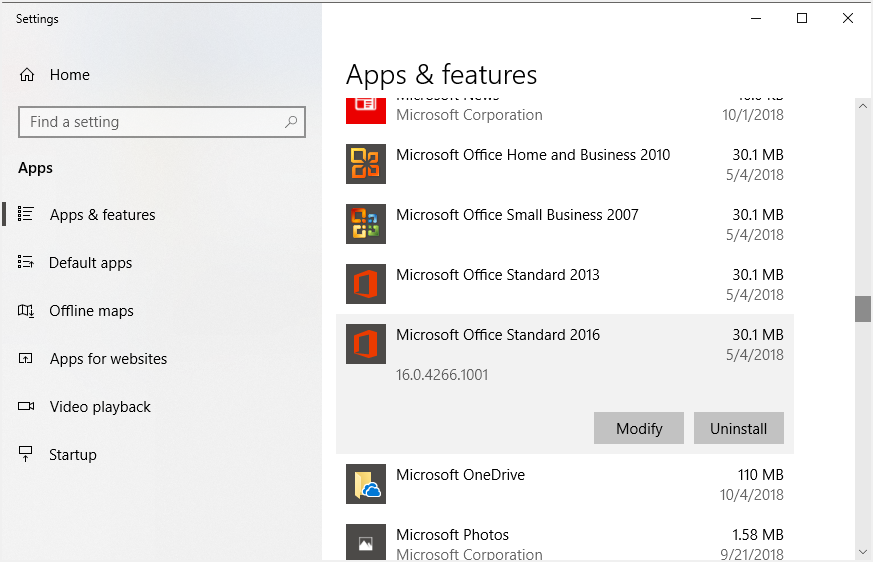

#Microsoft project professional 2010 full version promotional label how to

That’s why I don’t presume to predict - history is a lesson in complexity not predictability - but what I do feel I’ve learned to understand, thanks to my studies, are the mechanisms of historical change, the how of history’s dynamism rather than the what next. So, in the middle of so many discussions of the causes of this year’s events (economics, backlash, media, the not-so-sleeping dragon bigotry), and of how to respond to them (petitions, debate, fundraising, art, despair) I hope people will find it useful to zoom out with me, to talk about the causes of historical events and change in general. But on the ground it must have felt exactly the same, the real peace and those blips. I keep thinking about what it felt like during the Wars of the Roses, or the French Wars of Religion, during those little blips of peace, a decade long or so, that we, centuries later, call mere pauses, but which were long enough for a person to be born and grow to political maturity in seeming-peace, which only hindsight would label ‘dormant war.’ But then eventually the last flare ended and then the peace was real. I feel the same shock, fear, overload, emotional exhaustion that so many are, but at the same time another me is analyzing, dredging up historical examples, bigger crises, smaller crises, elections that set the fuse to powder-kegs, elections that changed nothing. There is a strange doubleness to experiencing an historic moment while being a historian one’s self. Is progress inevitable? Is it natural? Is it fragile? Is it possible? Is it a problematic concept in the first place? Many people are reexamining these kinds of questions as 2016 draws to a close, so I thought this would be a good moment to share the sort-of “zoomed out” discussions the subject that historians like myself are always having.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)